Feeling A Bit Sheepish

By Bekhi Spika

"Sheep, like people, are ungovernable when hungry." -John Muir

My parents live 20 miles from Lewistown on a sheep farm. Well, it’s lots of things; a rescue ranch for horses in their twilight years, a kickass garden, and a place where single cats like to mingle. But in terms of the hard work, it is a sheep farm. As a kid, I spent a lot of time feeding bum lambs, sorting sheep (why are we sorting them again? Is it like food and water, where sheep need to be sorted to grow big and strong?), and, of course, preparing for the event of the year: shearing.

I wasn’t a fan of shearing until I moved back to Lewistown after being in the “big city” of Minneapolis. It was strange; there was something incredibly comforting about being a part of the ceremony each year. I’m not sure why I found it to be this desirable experience, because most of the shearing experience isn’t about the shearing itself, but rather the getting ready for shearing part. There’s an honest-to-god checklist that you must follow in order to be ready for the big event:

1. Spend at least a week cleaning out the barn and reorganizing the shoot to make sure the sheep don’t boogie out of line.

2. Accidentally hit one of the beams in the barn with the Bobcat while cleaning and spend an extra day at the last minute fixing the broken beam so the barn doesn’t collapse during shearing.

3. Invite a get-shit-done aunt over two days prior to help clean the house so when the shearers come up for the 45-minute lunch break, they don’t think we're the slobs that we are.

4. Invite another get-shit-done aunt over to do the cooking for what I like to call Thanksgiving in May, which consists of at least two pork roasts, 32 potatoes, four pounds of broccoli salad, three homemade bread loaves, one turducken, 13 noodle salads, half a dozen pies and a pan of 7-Layer Bars.

5. Force the family to arrive at the barn no later than 3 hours prior to the shearer’s arriving, because they are prompt people and we can’t be our standard sloppy selves when they get here. Wander around aimlessly until they arrive.

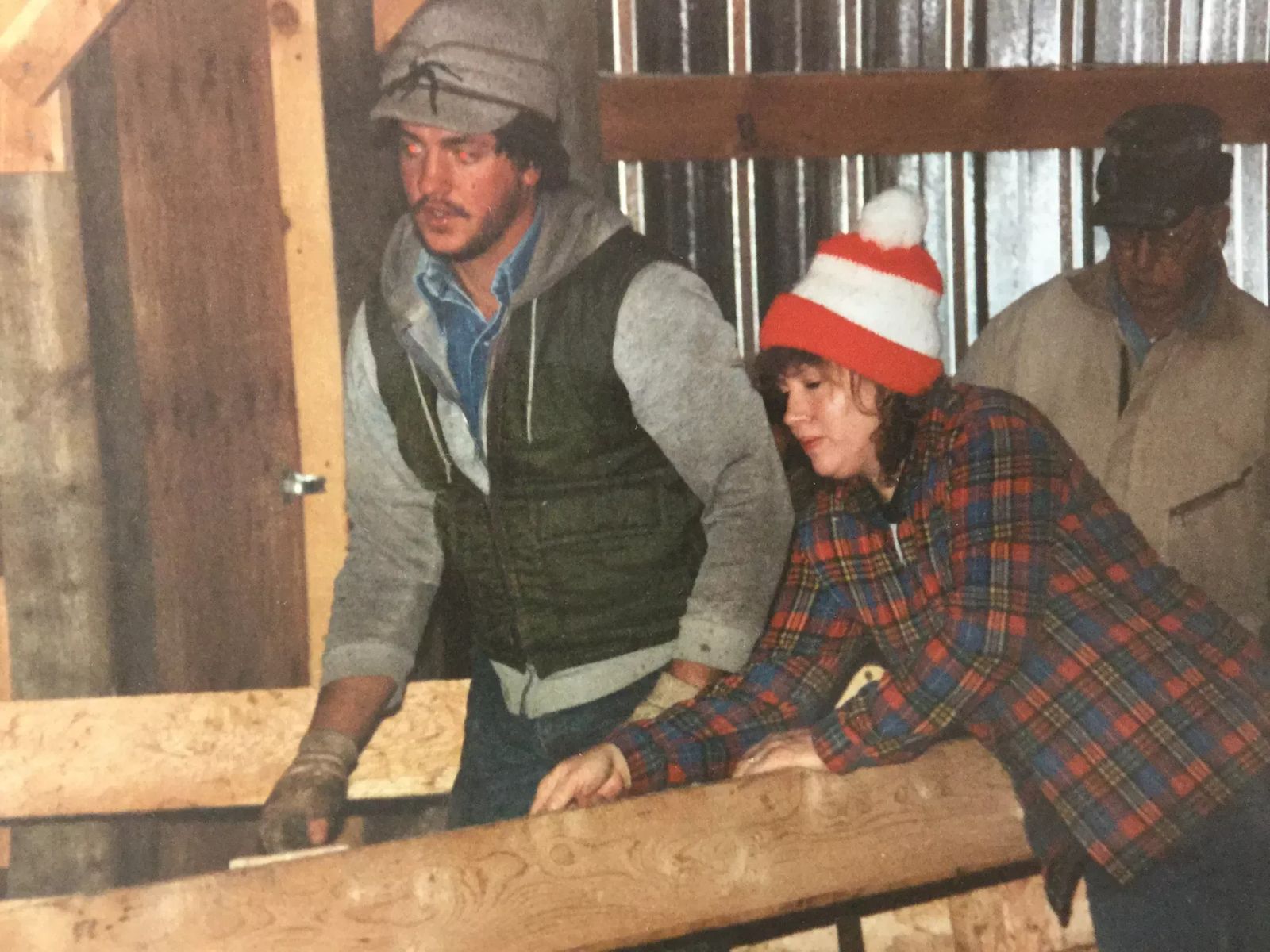

Shearing at the Spika farm back in the 80s

When things are finally in place and the shearers are all set up, the sheep go every wrong way possible until they meander into the chute and get ushered up the ramp into the shearing trailer. Here, 4-5 men (and sometimes women) are waiting inside with buzzing razors and sweaty brows. You don’t really get much of a glimpse into the shearing trailer while things are happening, but you know they’re literally working their asses off. From my point of view, shearing is a lot like trying to put a pillow into a pillow case, only the pillow is at least 100 pounds, and the case is the size of a glove, and there are feet coming out of nowhere kicking you in the face.

I realized when I moved back and started living the sheep life again that I really had no clue what the sheep and shearing industry was even about. My parents told me that back in the 80s and 90s, shearing was sort of a community event. Lots of our neighbors would bring their flocks to our barn for and entire day's worth of work. Then something happened...sheep prices went down, wool prices went down, people started consuming less lamb and synthetic fibers became more mainstream. I even read one statistic that said over the last 25 years, the number of sheep in the nation has been cut in half.

So I asked Josh Ridgeway, the fearless leader of Ridgeway Shearing, if he could shed a little light on the industry and the future of his profession.

Inteview with Josh Ridgeway, Ridgeway Shearing

The below pictures are of Josh and his 16-year-old son, Cody. Cody has been helping shear for a few years but is usually on wool duty. This year is his first year doing the shearing. Notice that in this picture, Josh is literally holding Cody’s hand and guiding him along. Definitely a family business!

Q: What made you want to be a shearer?

When I was young, I got asked to come along. At that age, I was broke and decided to give it a try. Once I started, I realized it was for me. The self-motivation and satisfaction from doing something not a lot of people can or want to do was my motivator.

The man that made me who I am and made me become the shearer I am today is Keith Bratton. He gave me the inspiration and the knowledge through his time and unconditional effort for the sheep and sheep men. He’s the reason I’m in the position I am in today to carry on the shearing industry and ensure the futures of our family of shearers that continue to work with Ridgeway Shearing.

Shearers are very family orientated and consider one another family. We stand beside each other through thick and thin and want the best for each other.

Q: What makes a good shearer? How does one break into shearing?

A sheep shearer becomes a shearer only after letting go of everything they think they know. Walking into the plant and grabbing your first sheep is like learning how to walk for the first time. The sheep will beat all of your pride and intelligence that you thought you had right out of you; and when you are broke both mentally and physically, that’s when an old school shearer is standing beside ya coaching you on how to get through it and giving you the confidence to keep going. A good sheep shearer is not made over night. It comes through hard mental and physical work and support from the sheep shearing family.

I have had the cream of the shearing industry and have learned from exceptional shearers that taught me along the way. Shearing does not come easy and cannot be taught to just anyone; it takes a unique person to become a shearer. You need to have strong self-motivation, the ability to constantly learn new techniques, and dedication and devotion.

Q: What is the best thing about shearing?

Food, family, being a part of all of the great families that I shear for. Words cannot express how good it feels to shear year after year and be involved in the lives of so many people; I get to watch kids grow up, I'm a part of family stories and gatherings, and countless people welcome me into their homes. The sheep themselves appreciate me too. Not only am I able to produce a valuable marketable product for the sheep men and communicate with them about the animals’ wellbeing, I also help the sheep by removing that bulky wool.

Q: What's the worst part?

It’s seasonal and there are lengthy stints of time being away from home and family. Also, gas prices.

Q: What's the worst injury you've ever had?

Obviously working with animals and sharp tools involves injury. The physical and mental scars are daily reminders to me of the pride and joy I get out of doing what I love and being able to call myself a sheep shearer.

Q: I've heard this community used to have a ton of sheep ranches but in the past few decades, sheep ranching has sort of died down. What was the shearing profession like back when sheep ranchers were everywhere, and how does it compare to now?

In the past, the shearing season would last up to 8 months and you would only have to travel 100 miles a day on average. A sheep shearer today is lucky to get 3-4 months of consistent shearing and has to travel upward of 200-300 miles a day to get the sheep. On average, a shearer will get 100-150 sheep per day. Shearer’s expenses have also increased dramatically due to travel between jobs and number of sheep at each place.

Q: What does the future of shearing look like?

That is a two-part question. On the personal side, Ridgeway Shearing will be here until I cannot stand up anymore. It’s in my blood and is something I have so much passion for that I will never quit. I not only enjoy doing it myself but I really enjoy teaching others how to do it and watching them try to keep up with me.

On the professional side, the future is unknown. As generations take over or ranches are split, sheep numbers keep declining. So as the surviving shearers of the sheep industry, we do our best to keep a positive outlook and keep grabbing the next sheep to come through our turn-out shoot.

Q: Do shearers have better bodies than fire men?

I’m not sure. I can’t say I have ever checked out a fireman’s body. I can say that shearing is very physical. It requires a lot of stamina and strength to hold the animal and maneuver it while removing the wool. My wife has no complaints.